Disclosure Programs:

Do they protect patients — or the bottom line?

A momentous change has taken root in the medical industry. Rather than deny or defend medical errors, a growing number of hospitals have adopted a more proactive approach: medical error disclosure programs in which they admit errors upfront.

In 2001, Mr. Rick Boothman, chief risk officer at University of Michigan Health (UM), introduced “The Michigan Model.” Aiming to make litigation a last resort, he promised that along with disclosing the error, UM will explain why it happened, apologize, offer fair compensation, and learn from the mistake.

Boothman soon became the nation’s foremost promoter of disclosure programs, and The Michigan Model evolved into what is now known as a communication and resolution program, or CRP. While he promotes it as an ethical and transparent approach that serves to protect the patient, in practice, there are flaws in the model that enable UM and the many hospitals following in its footsteps, to protect their profits instead.

1) The Selective-Disclosure Gap: Rather than disclose all medical errors, the model leaves hospitals free to cherry-pick which errors to disclose. Selective disclosure is described in a prominent Harvard study as hiding errors that are “likely to trigger lawsuits, cost a lot, or both.” It may also mean the selective use of the components of a CRP, rather than employing the entire program as a bundle, as it was meant to be. And it may mean hiding errors that the patient is otherwise unlikely to discover or that, like mine, might involve a high-profile, high-volume physician.

2) The Conflict-of-Interest Gap: While risk managers protect hospitals financially, the model also requires that they offer harmed patients fair compensation. These competing objectives require harmed patients to “take it on faith” that the risk manager will act against the hospital’s financial interests, and instead will “fully and fairly” compensate them.

3) The Transparency Gap: One of the stated core value of CRPs is transparency, and yet hospitals with CRPs routinely discharge their patients without providing any information about their disclosure program. They even fail to disclose that they have a CRP.

The first two gaps are known vulnerabilities in disclosure programs, but the transparency gap is not. I first encountered it as a patient at UM, and later, many times, in my own research. And, because I refused to sign a confidentiality agreement, I am free to use my own experience at UM to discuss some of the ways in which disclosure programs with great potential can be subverted in the implementation.

* * *

The Medical Error

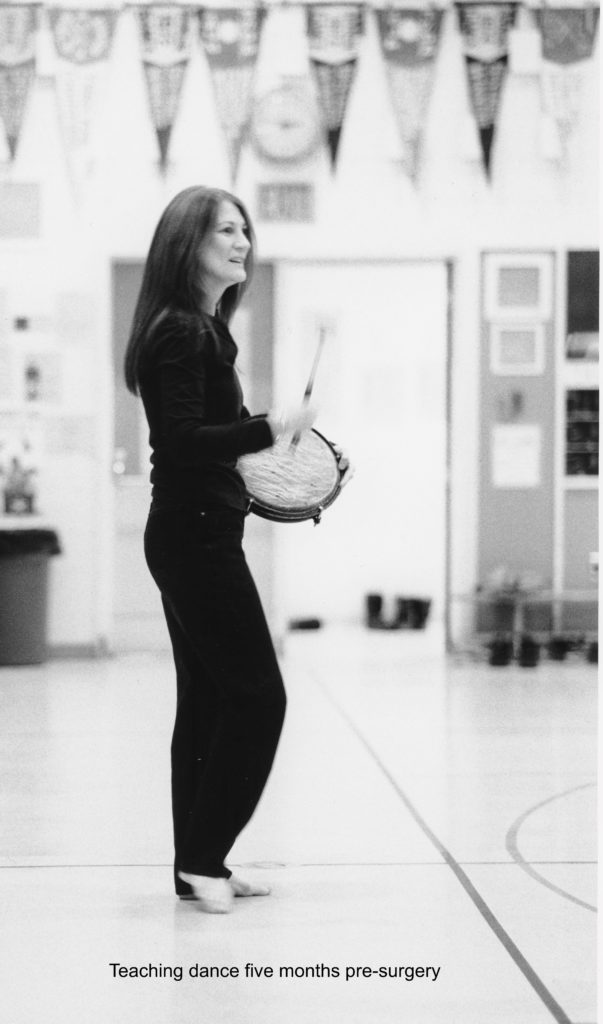

I was a professional dancer, choreographer, and teacher, but now I can’t balance on one leg, even for a few seconds. In 2004, I traveled from my home in Toronto, Canada to UM to have a small, benign brain tumor removed by an internationally recognized neurosurgeon. Despite my efforts to receive the best possible care, I left with the tumor fully intact and most of my healthy pituitary gland removed — a significant error apparently perpetrated by an unsupervised physician in training.

The surgery resulted in a cascade of debilitating hormonal deficits, and a life-threatening complication resulted in permanent brain damage affecting how I talk, think, and move. Yet, despite the pathology report confirming the error, UM failed to disclose it — they also failed to inform me that they had a disclosure program.

Because brain damage is classified as one of the most serious injuries, the Michigan state legislature adjusted the allowable compensation in cases like mine, to be much higher than for other damages. A risk manager, therefore, would calculate my damages as especially costly. And rather than pay for costly errors, a hospital practicing selective disclosure may choose not to disclose it.

Instead, it may select the small mistakes: it’s cheaper to pay a small settlement than pay for lawyers, expert witnesses, travel, and court costs. Similarly, the hospital may choose to disclose obvious errors like leaving a clip in a patient during surgery: it’s cheaper to pay for the mistake rather than invest in an unwinnable case.

Searching for Answers:

My next 18 months were filled with tests and consults with specialists who eventually found the cause of my many alarming symptoms. MRIs revealed that the surgeon (or more likely, the unsupervised resident), removed all but a small fragment of my healthy pituitary gland. He sent five pieces to the lab clearly labeled as “pituitary tumor.” But the lab results confirmed that while the surgeon thought he had removed the tumor, the specimens proved to be pieces of normal pituitary tissue.

Also notable was that my surgeon failed to document the error in the operative report. He even failed to disclose it anywhere in my 170-page medical record. And when I prepared to see another surgeon to remove the tumor, he offered to send “a copy” of the report. But, instead of sending a true copy, he sent an altered version — by replacing several key technical terms, he effectively masked the error.

Failing to document the error and altering a medical report are both grounds for license revocation. In addition, altering a medical report is a violation of Michigan’s criminal law — a felony. And that’s when I got a lawyer and filed a claim against my surgeon. Mr. Boothman sent a five-page response, but again failed to mention UM’S disclosure program. The same omission occurred in every subsequent communication he sent.

The Mediation in Retrospect:

Four years after the surgery, UM arranged for me to participate in a mediation. Although this was part of their usual disclosure process, I remained unaware that they had a CRP or that I was participating in it. Now, however, with the knowledge I’ve since gained about the Michigan Model, I see how Boothman violated both the letter and spirit of his program.

Most damning for the defense were the steps my surgeon took to conceal the error. Boothman, an experienced malpractice defense lawyer, would know that failing to document the error and altering a medical report are widely considered the kiss of death for any malpractice defense. In an article published in “The Legal Examiner,” David Mittleman writes, “Doctors and hospitals will sometimes rely on false, misleading, and disingenuous medical records to avoid being held responsible for their mistakes. Not only is this a felony in most cases, it is becoming increasingly clear that courts will not let wrongdoers get away with covering up their errors.”

And, when I spoke with Ms. Deborah B. Willis, a lawyer and Risk Management VP for a physician’s liability insurance company (SVMIC), she added, “The fraudulent alteration of a medical record virtually destroys any chance of successfully defending a medical malpractice claim … Juries generally give physicians the benefit of the doubt when it comes to issues of ‘medical judgment’ but will not forgive any appearance of tampering.”

Yet old habits die hard. Boothman submitted a mediation summary in which he denied and defended the altered operative report by falsely claiming that a resident had written the report (that my surgeon was merely correcting the resident’s errors). The hospital’s defense, however, is contradicted in black and white: at the bottom of the report, the name following the words “Dictated by” and “Electronically signed by” are the same and written in capital letters: Dr. William F. Chandler. No resident’s name or initials appear anywhere in the document.

Boothman was faced with: 1) the lab report confirming the error, 2) Chandler’s failure to document the error, and 3) the altered operative report. Yet, he steadfastly maintained that there was no error or wrongdoing. After eight exhausting hours, he blind-sided me with multiple personal attacks: he mixed baseless assertions with twisted partial facts to characterize me as a deceitful opportunist. Next, he claimed that the maximum he was authorized to offer me was $125,000, however he was willing to ask his supervisor for permission to double that amount — but only if I would agree to it beforehand. Thoroughly drained, fighting tears, and desperate to get out of there, I failed to realize that as chief risk officer, Boothman wouldn’t have a supervisor. I was outsmarted, and agreed to a settlement that was only a tiny fraction of what damages like mine typically warrant.

I later learned about verdictsearch.com, the leading provider of verdict and settlement research that searches a comprehensive database of real jury verdicts, legal judgments, and settlements in the U.S. According to the 61-page report they provided to me, compensation for a woman of my age, with my type of brain injury, is typically between $5 million and $10 million — I received $250,000.

People often ask why my lawyer didn’t help me. The answer is that my lawyer had me sign an unusual contract; it stipulated that if there was no settlement, he would not take the case to court. (Cases involving neurosurgeons are exceptionally expensive — too expensive for my lawyer’s four person law firm.) This meant that if I didn’t settle during the mediation, he would receive no compensation whatsoever for all the hard work that he had done on my case during the previous two years . In short, he was highly motivated to get me to settle.

Patient JW:

In How Medical Apology Programs Harm Patients, Gabriel Teninbaum tells the story of patient JW to demonstrate the disparity between what UM offered as “fair compensation,” and what she would have received in court. I include it here because, her experience resembles mine.

Using the standard formula, UM calculated that JW’s case would settle for somewhere between $2,635,000 and $3,145,000 in court. But, when JW came to a doctor/patient meeting with her husband and her lawyer and asked for $2 million, UM accused JW of “being ‘unreasonable’ and inflating the value of her claim.” When she asked for less than half of the expected settlement range, they turned her down again. Despite her lawyer’s help, she ended up with $400,000 — less than 1/7th of what UM had calculated was warranted. The hospital’s offer to JW was only 14% of what she would likely have received in court.

Chasing the Transparency Gap:

My research odyssey began a year later when a friend sent me an article about disclosure programs and Boothman’s role in developing them. Over the next several years I read many dozens more articles. Eventually, I created this website in which I tell my story and invite other harmed patients or their families to tell theirs.

I’d always assumed that UM’s failure to tell me about its program was an isolated oversight, so I was stunned to receive two dozen heart-wrenching stories about medical errors — yet not one knew whether their hospital had a disclosure program. I found this so incredible that I called their hospitals and asked if they had a disclosure-type program. Most eluded my simple yes/no question saying that they weren’t sure, they didn’t have time to talk, they felt uncomfortable talking about it, or that they weren’t authorized to answer that question. Some simply hung up on me.

And, when I called The Joint Commission to confirm that the public has a right to know, I learned that we do not. The Commission requires hospitals to disclose all unanticipated outcomes, but the presence or absence of a disclosure program is voluntary and, astoundingly, can be kept confidential.

Dissatisfied, I hunted through the many newspaper articles I had collected about disclosure programs and realized that while hospitals routinely fail to inform patients about their CRP — they tend to be forthright with journalists. This enabled me to identify 33 hospitals with programs, but when I checked their websites, I discovered that information about their CRP, if provided, was tricky to find. It required using the search function along with specific, nuanced, words or phrases (for example, Stanford’s program is called PEARL). This means that to learn about the program, patients would have to already know that it exists. This lack of transparency suggests that rather than a rarity, failure to inform may be a standard feature of the disclosure program model.

Especially tragic is the case of Talia Goldenberg; she was only 23 years old when elective surgery at Swedish-Cherry Hill Hospital in Seattle resulted in her unnecessary death. After her surgery, Talia’s airways swelled and she couldn’t breathe. The shocking series of mistakes and negligent acts that caused Talia to suffocate are described in a Seattle Times article. Yet, the hospital did not disclose to her devastated family, the errors that caused young Talia’s death. It took over a year, calling once each month, for me to confirm that, in fact, Swedish-Cherry Hill had a CRP in place before Talia’s death. *

The Transparency Paradox: Why Hide Disclosure Programs?

By concealing their disclosure programs, hospitals are in the best position to control which errors come to light. As all risk managers would know, a well-known Harvard study determined that less than 2% of injured patients actually sue. Further research found that one common cause for the low rate is ignorance — most medical error victims fail to realize that they have received negligent care. If hospitals can avoid alerting their unsuspecting patients and their families to the possibility of malpractice, the hospital will be in a better position to protect their bottom line. **

Although Boothman asserts that reducing costs is not the primary goal behind their policy, the program has resulted in a large reduction in costs for the hospital. An early study published in 2010 found that after implementing their model program, UM’s claims dropped 36 percent, and lawsuits dropped 65 percent. The monthly cost of total liability and patient compensation dropped 59 percent, and legal costs dropped by 61 percent. And, according to Boothman, claims levels and numbers have continued to decline since the 2010 study.

Closing the Gaps:

Hospitals maintain that disclosure programs help medical error victims to heal. But, in my experience, since hospitals can easily use the gaps to avoid being held accountable, the patient often ends up doubly victimized.

The probable outcome of addressing the gaps would be a marked increase in hospital costs. This leaves hospitals with a hard choice: will they take the principled and honest approach? Or will CRPs regress into business as usual?

Rick Boothman left UM in June 2018. He has since formed a private consulting group in which he advises hospitals, governments, and insurance companies on the implementation of disclosure programs based on the Michigan Model.

*I have permission from Naomi Kirtner to tell the story of her daughter Talia’s death at Swedish-Cherry Hill Hospital in Seattle Washington.

** Hospitals who want to implement a CRP are currently being taught to provide an institutional policy or commitment statement about their CRP, and that the final document should be shared with families and patients as well as the community. And yet, it’s worded so that providing it on the hospital’s website — with no explanation as to how to find it on the website — fulfills the obligation.

See One More Disclosure Gap: Loophole in the law

Keywords: “Michigan Model”; “Apologygaps.com“; “Communication and Resolution Program”; “CRP”; “disclosure program”; “medical error disclosure program”; “disclosure, apology, and offer program”; “medical error”; “patient safety”; “patient advocate”; “Gail Mazur Handley”; “Gail Handley”; “gail@disclosuregaps.com“; “gail@apologygaps.com“; “elective-disclosure gap”; “conflict-of-interest gap”; “transparency gap”